It was the best of ads . . . It was (among) the worst of ads. . .

Rare is that television ad that has been more polarizing than the “Hey, Dummy!” CareerBuilder.com commercial from the 2009 Super Bowl.

Four years after its appearance, a writer for the Inbound Marketing Blog, still clearly irked by it, penned a piece in 2013, ranking it among the “10 most annoying ads of all time.” (And at the end of the article, the writer expands the criterion for his list from “most annoying” to, simply “the worst ”). Detroit Free Press columnist Julie Hinds listed the ad under the heading, “Grossest display of workplace despair,” and suggested that a segment of the ad “might be enough for the company to find a new ad agency.” And PC World simply described the ad as “crappy.”

Yet Innerscope Research, which employs an integrated approach to neuroscience consumer research, rated the 2009 CareerBuilder ad as the most “emotionally engaging” ad of that year’s Super Bowl – and one of the most engaging Super Bowl ads it has studied. And as far as we know, Innerscope is the only research firm to cite it as the top-scoring ad of that Super Bowl.

If you recall, the ad begins by presenting a series of fairly disturbing images: a woman in vocational distress screaming in her car followed by an employee being humiliated by his boss (“If you hate going to work and your co-workers don’t respect you. . .”) – and then the ad repeats those scenes and piles on the employee abuse four more times (along the lines, ironically, of The 12 Days of Christmas). Almost all the images are horrific, and the repetition of the lines is undoubtedly grating to some.

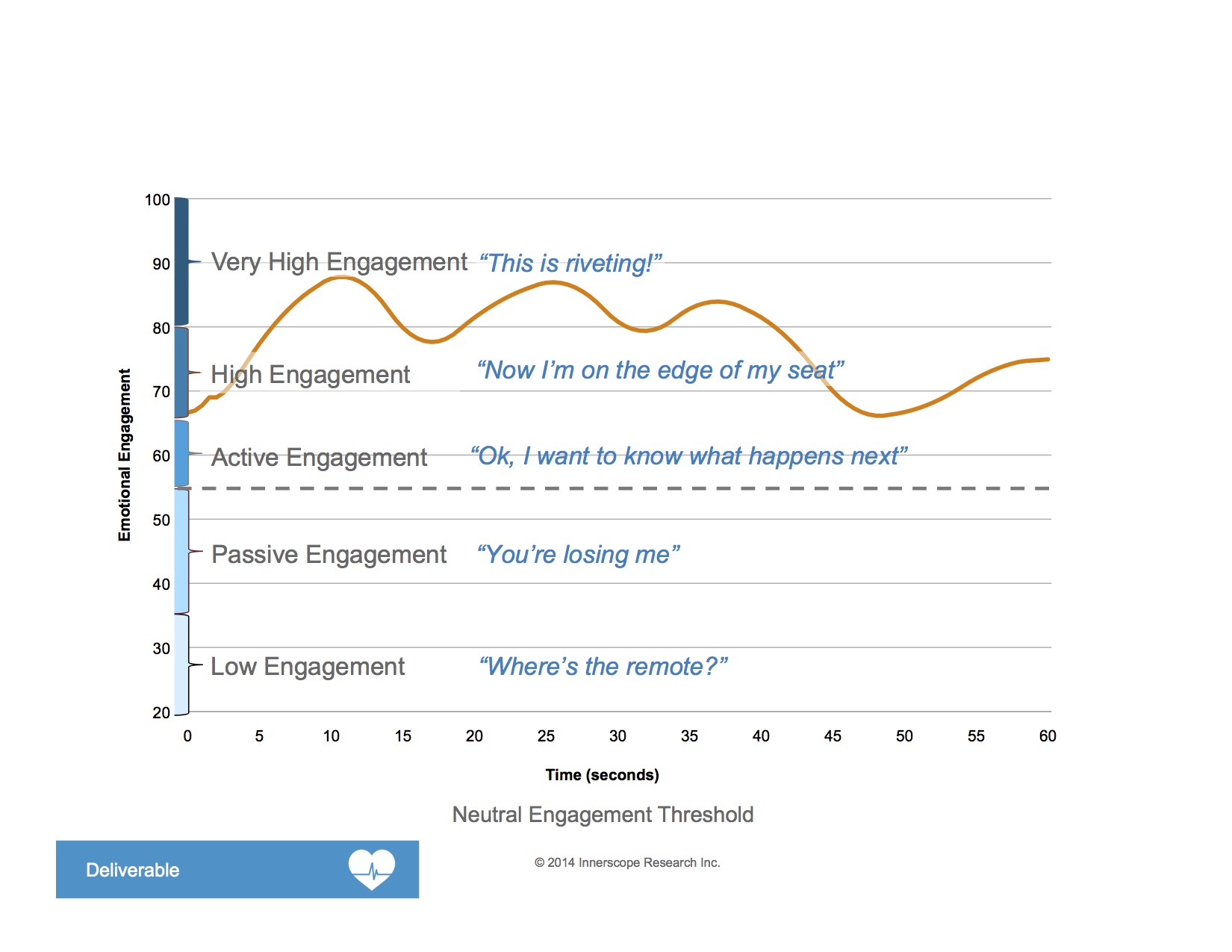

Before diving into the specific results, a little background: Innerscope collects biometric signals from respondents through devices that measure nonconscious biological responses that reflect the respondent’s emotional reactions to the ad. It then aggregates them on a moment-by moment basis throughout the commercial – and plots them graphically in terms of the time scheme using what we call an “engagement trace.” The results are easy to interpret: the higher the levels of Biometric Engagement, the greater the emotional involvement with the stimulus. The client whose ad produces an engagement trace that lingers in the area above 65 and into the 70s has good reason to be pleased.

This is the engagement trace for CareerBuilder:

The trace displays a roller coaster of an emotional journey, which probably reflects the fairly extreme reactions to the ad (more about that in a moment). Engagement rises immediately and steeply to rare, nose-bleed heights – and then drops precipitously – only to rise and drop several more times throughout the course of the ad.

That a highly successful ad would display such a varied, up-and-down pattern might be surprising to some, but there are three characteristics of this engagement pattern that Innerscope looks for in a successful ad. First, the peaks that it reaches are considerable. Relatively unusual is the ad that reaches a level of 80 on the emotional engagement scale. CareerBuilder’s “Hey, Dummy!” climbs as high as 90 and overall engagement dwells for a great portion of the running of the ad between 80 and 90, rare air indeed for most ads and rarer still for a :60s ad in the Super Bowl!

Second, the variation in scores, itself, bespeaks an audience that is actively involved with the progress of the ad. The pattern indicates that the audience is truly paying attention – and responding with considerable feeling. This audience rises to a substantial level of excitement not just once during the ad, but four times, indicating a deep level of interest and involvement with the ad. (If you’re not really paying much attention and aren’t emotionally involved, your biometric signals are far more likely to be relatively flat. The term “volatile” speaks volumes about a pattern like this – and about heightened levels of engagement). And last, the ad displays a final characteristic of most successful ads that we have tested: Engagement rises to a very healthy level during the last quarter of the ad, leaving the audience, literally, on a high note during the key branding moment.

And what does this ad have to teach us about the elements of successful advertising? Consider these three points:

1. Be wary (very wary) of what people consciously report about an ad.

This may be the most important message from consumer neuroscience research: what people say about an ad very often does not reflect their feelings – not because they are liars, but simply because what registers with the conscious mind is very often different from what registers nonconsciously and with a long-term (and sometimes unrecognized) emotional impact.

In The Righteous Mind, psychologist Jonathan Haidt likens the relationship between the rational forces and the emotional forces to a rider (conscious reason) on an elephant (automatic responses, intuition). Haidt argues:

“Automatic processes run the human mind, just as they have been running animal minds for 500 million years . . . When human beings evolved the capacity for language and reasoning at some point in the last million years, the brain did not rewire itself to hand over the reins to a new and inexperienced charioteer. . . Therefore, if you want to change someone’s mind. . . talk to the elephant first. . .”

The beauty of using neuroscience as a means of testing consumers’ reactions to advertising is that it is all about talking to the elephant. And the CareerBuilder ad is similarly oriented toward the pachyderm.

2. Do not underestimate the positive effect of good timing and context.

CareerBuilder may have created the perfect ad for its time. The ad, it should be reiterated, appeared in 2009, a year of considerable financial upheaval – and one of the most woeful years for job hunting in America’s recent history. An ad that offered hope for new and better possibilities in the job market appears to have been the perfect antidote for the consumer for an ill economy and a bleak job market. At the same time, the ad might not be as warmly received during plusher times – when it might be seen simply as annoying.

Great advertisements, like great leaders, are products of their times.

3. Ultimately, effectiveness is not always a function of overt likeability.

The ad is reminiscent of the infamous Charmin “Mr. Whipple” ads, which ran from the 1960s to the 1980s and for many represented one of the most loathed ad campaigns in history (and was the impetus behind a book entitled Squeeze This, Mr. Whipple). Loathed, it was, but it also sold product off the shelf.

The message: Sometimes annoying, repetitive ads can be disliked but strangely (to the nonconscious mind) engaging. The key to success for the advertiser is to generate a need state in the mind of the viewer – and it appears that with CareerBulder.com the need state was fairly ingeniously created when annoyance with the ad reminded viewers of annoyance with their jobs . . . which, in turn, the brand can fulfill and consumers can act upon.

The message: Sometimes annoying, repetitive ads can be disliked but engaging.

And, ultimately, the real question is: Does engagement translate into meaningful action? Consider this comment from PC World:

Let’s face it: Most people hate their jobs. It may be no surprise, then, that CareerBuilder’s crappy-career-shunning commercial makes the top of the list of the most viral Super Bowl ads. Nearly 3 million people searched for and watched the spot online. Bet the team who put it together won’t be out of work anytime soon.