I fell in love in March of 2014 … with a car ad.

The object of my affection goes by the name of “Buick Hmm” and its theme artfully recalls an earlier (some might say infamous) campaign for Buick’s former stable mate: “This is not your father’s Oldsmobile,” which some regard as a monumental failure. But Buick’s reenactment never explicitly makes the point that Oldsmobile tried to hammer into your head; rather it beautifully enacts the classic orator’s dictum, “Show; don’t just tell.” What’s more, Buick illustrates how craftsmanship and the right theme, well told, can create breakthrough advertising. It is similar to the Oldsmobile campaign, but so very different – and so vastly superior.

The object of my affection goes by the name of “Buick Hmm” and its theme artfully recalls an earlier (some might say infamous) campaign for Buick’s former stable mate: “This is not your father’s Oldsmobile,” which some regard as a monumental failure. But Buick’s reenactment never explicitly makes the point that Oldsmobile tried to hammer into your head; rather it beautifully enacts the classic orator’s dictum, “Show; don’t just tell.” What’s more, Buick illustrates how craftsmanship and the right theme, well told, can create breakthrough advertising. It is similar to the Oldsmobile campaign, but so very different – and so vastly superior.

The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge once described his conception of aesthetic greatness in poetry. He called it “multeity in unity.” Great works, he argued, have a lot going on – are complex – but find a way to unite complexity into a pleasing whole. And that’s what the Buick ad does. In 30 seconds, it masterfully weaves four vignettes into one clear, understandable, and demonstrable theme:

Today’s Buick is not what you think it is – and it is beautiful.

Those are, obviously, my own feelings and don’t amount to much for a company that was in bankruptcy not that long ago and needs a lot more than an enthusiastic response from one advertising researcher. Which is why the next phase of this love affair might be far more interesting: Neuroscience agrees with me. The Buick spot recorded higher overall biometric emotional engagement than 90 percent of TV ads that Innerscope Research measured this year.

And for those who would argue that the real measure of Buick’s success with this ad is in its financial performance: After the campaign broke in March. U.S. Sales were up 8 percent through August, compared to just 2.8 percent for all of GM.

Before diving into the specific results, a little background:

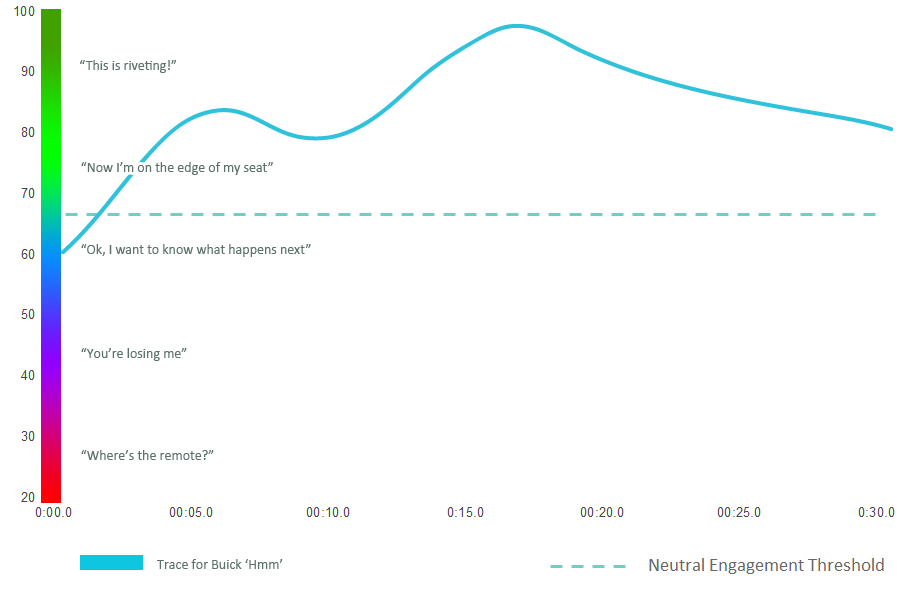

Innerscope collects biometric signals from respondents through devices that measure nonconscious biological responses that reflect the respondent’s emotional reactions to the ad. It then aggregates them on a moment-by-moment basis throughout the commercial – and plots them graphically in terms of the time scheme using what we call an “engagement trace.” The results are easy to interpret: the higher the levels of Biometric Engagement, the greater the emotional involvement with the stimulus. The client whose ad produces an engagement trace that lingers in the area above 65 and into the 70s has good reason to be pleased.

Now, here is the engagement trace for Buick Hmm, compared with average emotional engagement for ads that Innerscope has tested:

Notice that engagement soars immediately to the 80s, drops a bit, as is typical of effective ads, but remains in the high 70s – then shoots up to the 90s – and remains above the 80s for the last third of the commercial.

This Buick ad has achieved one of the highest overall levels of engagement that we have ever recorded.

And that’s all very nice, but the $64,000 question is, “What makes this ad so effective – and what can we learn from it?”

Over the past few years, Innerscope has been developing a series of Best Practices – which focus on the creative elements in advertising that we have found are consistently present in effective ads or that should be avoided based on the least effective ads. The Buick ad beautifully enacts a number of these best practices, and we thought it might be instructive to offer some explanations for this ad’s remarkable performance.

Tell a Compelling Story

So many of the most effective ads that we have measured offer a compelling narrative. Which ads have generated the most buzz after the Super Bowl? Almost invariably the day-after chatter includes enthusiastic comments about Budweiser’s touching stories of interspecies love (trainer and Clydesdale, puppy and Clydesdale) or poignant depictions of family gatherings.

Well-told stories lift the spirits and generate emotion, and Buick not only tells a story, but raises the ante with a four-part story featuring a diverse cast of characters that reinforces the main point with the same narrative elements: a) the main character fails to recognize that the attractive car that s/he is looking at is a Buick and b) when made aware of the oversight, the characters display awe and wonder.

Put in another way, the ad executes a proven formula: The first half of the ad poses the problem (Where is the Buick?). The second half offers the solution (The Buick is right here in front of your untutored and disbelieving eyes). As is typical of the most effective ads, when the solution is revealed, the grateful audience responds emotionally. That’s especially true if the solution is offered humorously, as it is in the scene in which the parking attendant discovers that the car that he has been frantically seeking has rested only a few feet away from him all along and “speaks” to him when his back is turned.

Note in the engagement trace shown below that this series of “reveals” (the solution to the mystery) is accompanied by an exceptionally steep rise in engagement.

Integrate the Brand Early and Often

Too many advertisers today hide their light under a bushel – and often and unwisely wait to announce their names only at the end of the ad, when many viewers have tuned out or run into the kitchen to grab a beer. The assumption is that TV audiences possess unlimited patience and view the commercial as they would a movie, happily waiting for the inciting incident and the denouement.

Years of advertising research suggest that nothing could be further from the truth.

This ad first mentions “Buick” early – at about the five-second mark – and then repeats it at least 10 more times. And that repetition of the name, rather than being annoying or boring, is the essential element of the ad’s humor.

As a result, no one who watches this ad walks away confused about who sponsored it – something that too few advertisers can say. The result, we would suggest, is one of the great goals of advertising: Arouse a strong emotional reaction, but link that emotion very early on with the brand.

It seems so easy – but so few advertisers pull it off.

Exploit the “Central Bias”

Innerscope’s extensive eye-tracking work clearly reveals a marked tendency among television-viewing audiences: The default position for their gaze is the center of the screen. Interestingly, many advertisers fail to take advantage of that bias and place important visual, story-telling elements in off-center positions – and then quickly cut away to another scene before the viewer has a chance to visually find the focal point.

But not Buick. The joke in the ad is that the characters don’t know a Buick when they see one, but the audience does – because the creators of the ad artfully and consistently place the car in the center of the screen so that the central bias ensures that the hood ornament is the most prominent element on the screen. And that strategic placement reinforces the joke (How can you not know that’s a Buick when it’s so obvious to me?) and bolsters the branding effort.

Note below in the heat map, which represents the findings from the eye-tracking work, the intensity of attention falls right on the hood ornament.

Keep it Simple

Though the ad features four vignettes, they all tell the same, simple three-part story: 1) That’s not a Buick; 2) oh, this is a Buick; 3) this is really nice (with feeling).

And the repetition of that simple message through a range of characters ensures that few viewers will walk away wondering what the point of the ad is.

It’s simple. It works.

One last, but extremely important matter. Innerscope’s research on this ad reveals some very impressive results, and the research is nicely corroborated by the sales figures for Buick. But is there any further evidence of the effectiveness of this ad employing other means of validation?

After seeing the impressive Innerscope metrics on the Buick ad, I called a Buick representative in Detroit, explained our interest and results, and then asked if he had any other metrics demonstrating the extent to which the commercial had an impact. He responded by explaining that the ad had been launched in March of 2014 and that since then their brand-tracking data, measuring breakthrough and brand recognition, have been “through the roof, ” which he attributed to the power of that near-ubiquitous ad.

And even though we are wary of using automotive-sales figures to bolster claims about ad effectiveness, we offer this excerpt from the November 3, 2024 New York Times:

At G.M., total sales were essentially flat in October, up 0.2 percent compared with October 2013, the company said. The Detroit automaker, which has been engulfed in a safety crisis and millions of recalls this yearwas dragged down by lackluster performance from its Chevrolet, GMC and Cadillac brands. Buick was the lone exception, up 6.5 percent.

Oh my!